How 1,600 used postage stamps ended an NBA front-office career

Sources on this case are scarce. No documentary, no podcast, no long-form investigation has revisited it since. Only a handful of period newspaper clippings make it possible to reconstruct what happened. There is also a single online article published by The Touchback in 2023. Not much material, but just enough to tell the story of a strange episode, one that begins with a general manager whose name already sounds slightly out of place.

A rising executive in Kansas City

In the spring of 1980, the Kansas City Kings are slowly returning to relevance. After just two playoff appearances over the previous thirteen seasons, the Kings are now coached by Cotton Fitzsimmons and coming off a strong 47-win campaign. The roster is young and promising. Otis Birdsong, Phil Ford, Reggie King, Scott Wedman, Bill Robinzine, Sam Lacey. Far from title contention, of course, but solid enough to envision several playoff runs. Add one or two pieces, and things could get interesting.

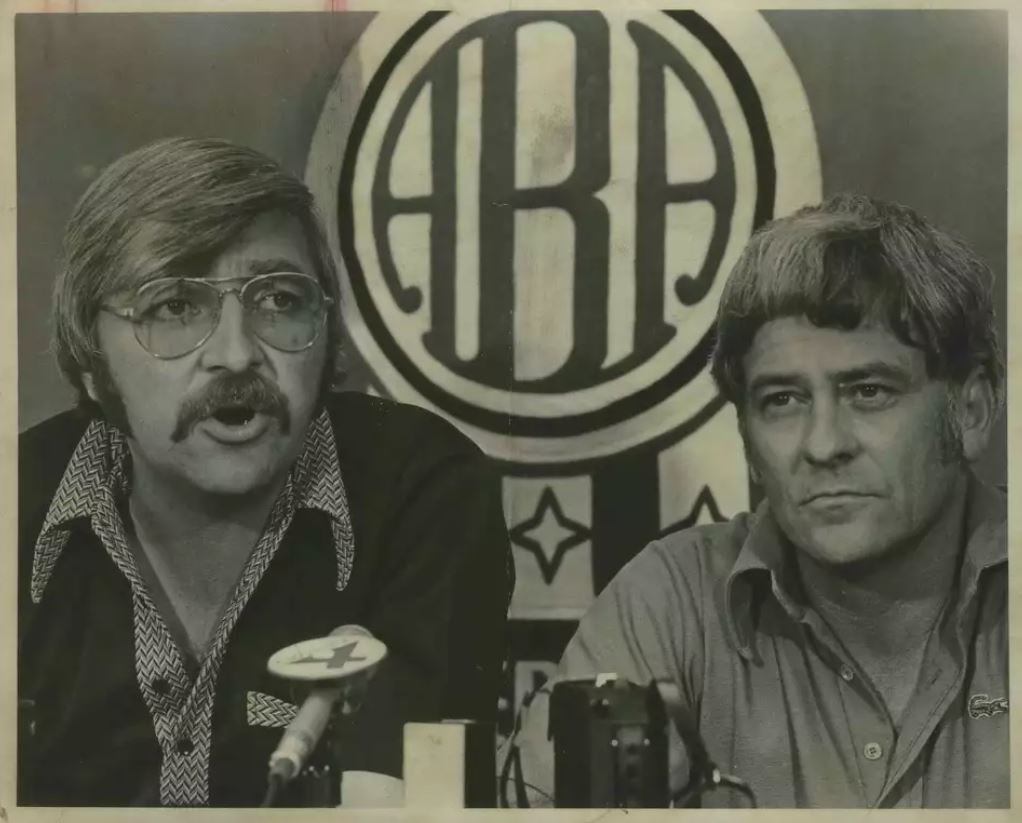

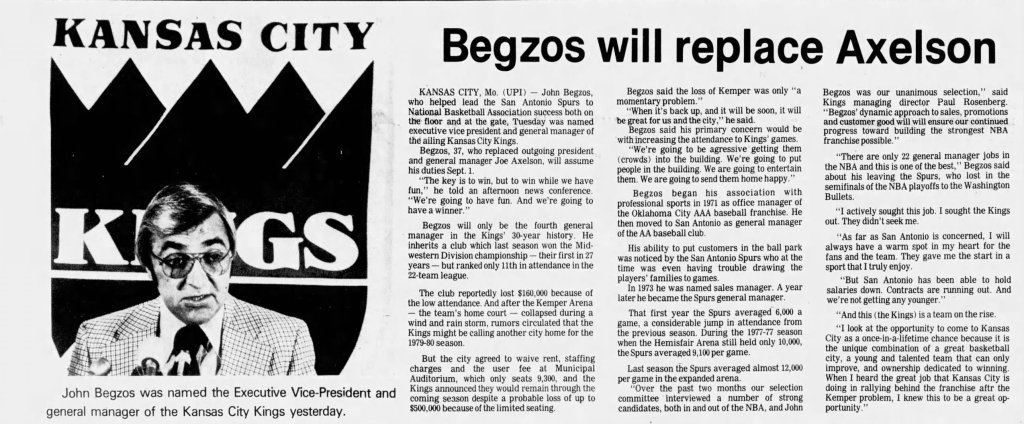

John Begzos is running basketball operations. He applied for the job himself. Appointed general manager in 1979 at just 37 years old, he arrives in Kansas City with a strong résumé from San Antonio. Five playoff seasons and a successful transition from the ABA to the NBA with the Spurs, along with steadily rising attendance figures. Young, ambitious, charismatic, he is given full basketball authority. He is described as an up-and-coming executive, somewhere between Don Nelson and Pat Williams. His philosophy is simple. Winning should be fun.

In San Antonio, he had helped create a supporters’ group, the Baseline Bums, a European-style fan section meant to energize the arena. A marketing-minded executive focused on fan experience. Exactly what a Kings franchise with declining ticket sales needed.

From the outside, the 1979–80 season unfolds smoothly. Begzos extends Fitzsimmons, keeps the core intact, projects stability. Behind the scenes, however, the seeds of trouble are already there.

1,600 stamps and a firing

In late October 1980, just days before the new NBA season tips off, the news breaks. John Begzos has been fired. The official statement gives no reason. Asked by the Kansas City Times, team president Paul Rosenberg Jr. deflects. “It’s neither a personality issue nor a basketball issue.”

Local reporters dig deeper and uncover an almost absurd story. Begzos allegedly purchased 1,600 postage stamps at half price through an acquaintance of his mother. The stamps, supposedly new, had already been canceled. He then resold them to the franchise at face value, about 120 dollars, saving himself a few dozen dollars in the process. And losing his job over it. A spectacularly bad trade-off. Straight out of a slapstick comedy.

Alerted by a suspicious employee and then by postal authorities, Rosenberg demands Begzos’s resignation. Begzos refuses and is dismissed. He later insists he acted in good faith and did not know the stamps were already used. When asked about the reasons for his firing, he claims not to know them.

An excuse, or a convenient pretext

Why such severity over a mistake valued at 120 dollars? The official explanation never truly comes. The franchise offers no public justification. Rosenberg simply speaks of a “change in direction” and refuses to elaborate.

Rosenberg temporarily assumes the GM role before appointing Jeffrey Cohen for two seasons. The lack of transparency fuels speculation. The stamp affair may have served as a pretext to remove a general manager considered too independent or at odds with ownership. But the abrupt dismissal remains a mystery. To this day, no fully convincing explanation has surfaced.

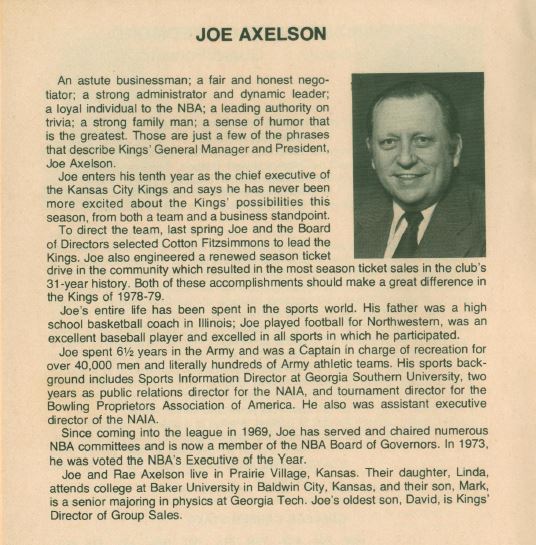

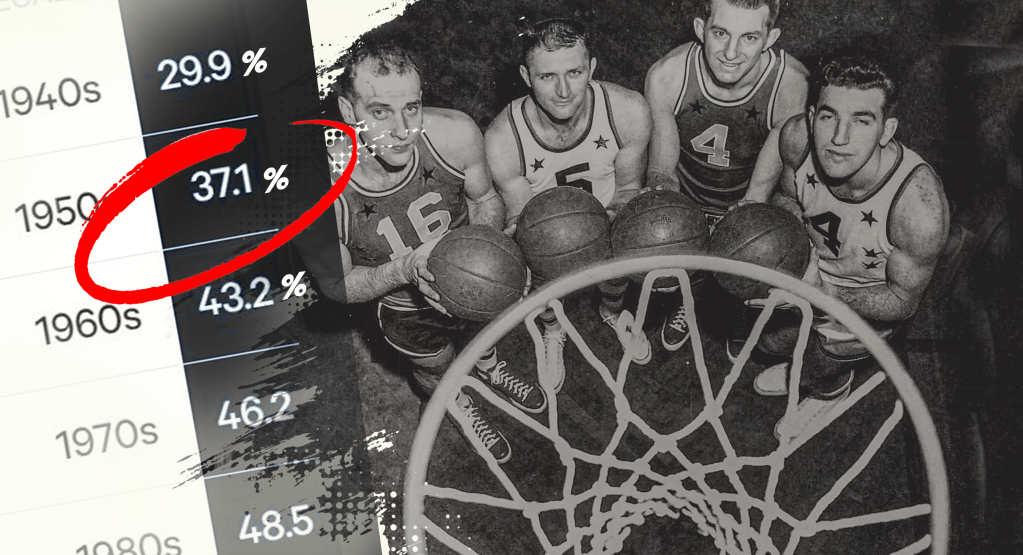

The comparison with Joe Axelson, Begzos’s predecessor and later successor, highlights the double standard. Despite highly controversial decisions, trading Oscar Robertson to Milwaukee for little, sending Tiny Archibald to the Nets, relocating the franchise from Cincinnati to Kansas City and Omaha, Axelson remained in place for over a decade. He returned as general manager in 1982 and would oversee yet another relocation, to Sacramento in 1985.

Over sixteen years running basketball operations, Axelson’s teams reached the playoffs just four times, never advancing past the first round, compiling a 3–17 postseason record. Begzos, meanwhile, was dismissed over office supplies.

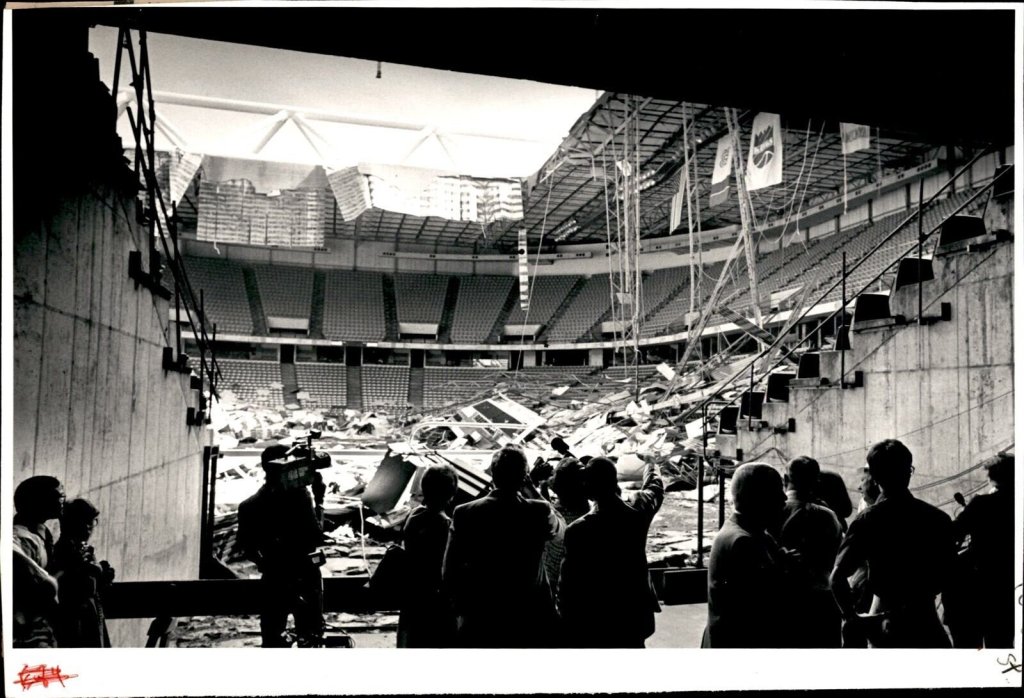

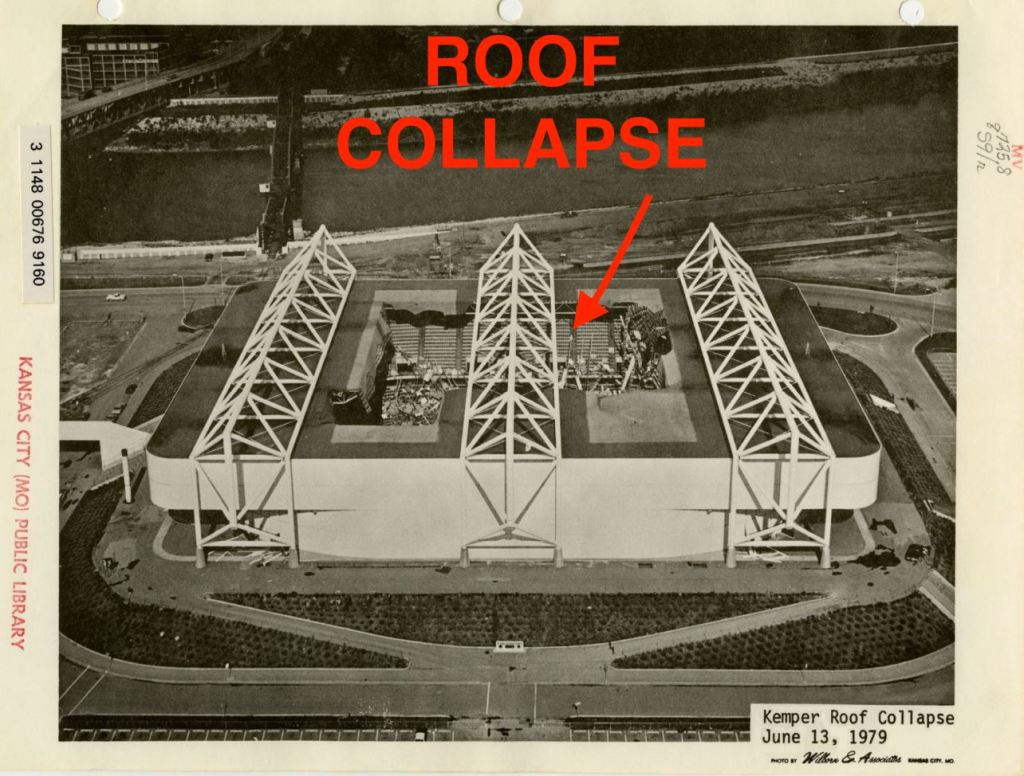

Some unofficial criticisms even blamed him for declining attendance at Kemper Arena, the Kings’ then state-of-the-art venue built in 1973. Except that just weeks before Begzos took the job, the arena’s roof collapsed during a violent storm, exposing major structural flaws in its suspended-roof design. The building was empty at the time, no injuries, but not exactly reassuring for fans considering a return.

Was Begzos too independent? Too ambitious? Did he alienate ownership or certain shareholders? Were his methods too borderline? Beyond the stamp affair, hardly a crime of the century, nothing particularly negative ever emerged about his management, either in San Antonio or Kansas City. He was described as authoritarian, but well within the norms of NBA front offices at the time.

The timing raises questions. Just weeks earlier, Begzos had approved a widely criticized trade, sending Bill Robinzine to Cleveland. An unpopular move, not insignificant for the player involved, whose tragic fate I previously detailed here. Still, nothing that remotely justified being thrown out over something as trivial as a minor postage scheme.

After the NBA, after the noise

Begzos does not let it go. He sues the Kings for wrongful termination and wins. Roughly 60,000 dollars are paid as part of a confidential settlement, reflecting a breach of the contract he signed in 1979. He never works in the NBA again.

His post-NBA career includes real estate, a Buffalo cable television channel, and a sports bar in Addison, Texas.

The trouble does not fully end there. In 1982, Begzos again draws legal attention, this time over a more serious insurance fraud case involving a burned property. He had cashed a 20,000-dollar check intended for the bank that held the rights to a fire-damaged house. He pleaded guilty and received one year of probation, narrowly avoiding prison.

John Begzos died in September 2004, at the age of 62. His life extended far beyond the strange episode that would come to define his NBA legacy. A decorated Vietnam veteran, he rarely spoke publicly about his service, and went on to lead several successful careers in sports management, from minor league baseball to the ABA, where he was named Minor League Executive of the Year in 1973 and played a key role in the NBA-ABA merger.

That is the story. Less a state scandal than a case of strangeness and absurdity. Fired over 120 dollars’ worth of used stamps, Begzos never had the chance to steady the self-proclaimed Kings and their cardboard crown. The franchise did not need his help to unravel anyway, continuing to flounder in Kansas City, Omaha, and later Sacramento.

Leave a comment