Understanding the unusually low shooting percentages of early professional basketball

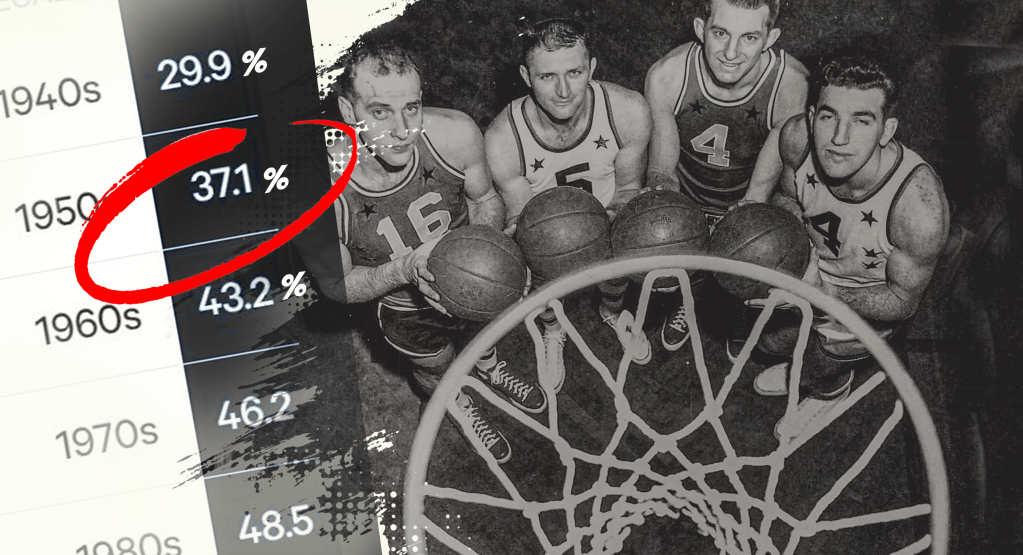

In an era dominated by the Minneapolis Lakers of George Mikan and Vern Mikkelsen, league-wide field goal percentage across the entire 1950s sat at just 37 percent. The dunce cap clearly found a home among the pioneers.

Individually, it took until the 1960–61 season and Wilt Chamberlain for an NBA player to finally reach the symbolic 50 percent shooting mark. It is worth noting, even if it seems obvious, that the three-point line was still decades away, not introduced until 1979.

So the question is simple. Were players in the 1950s just bad shooters?

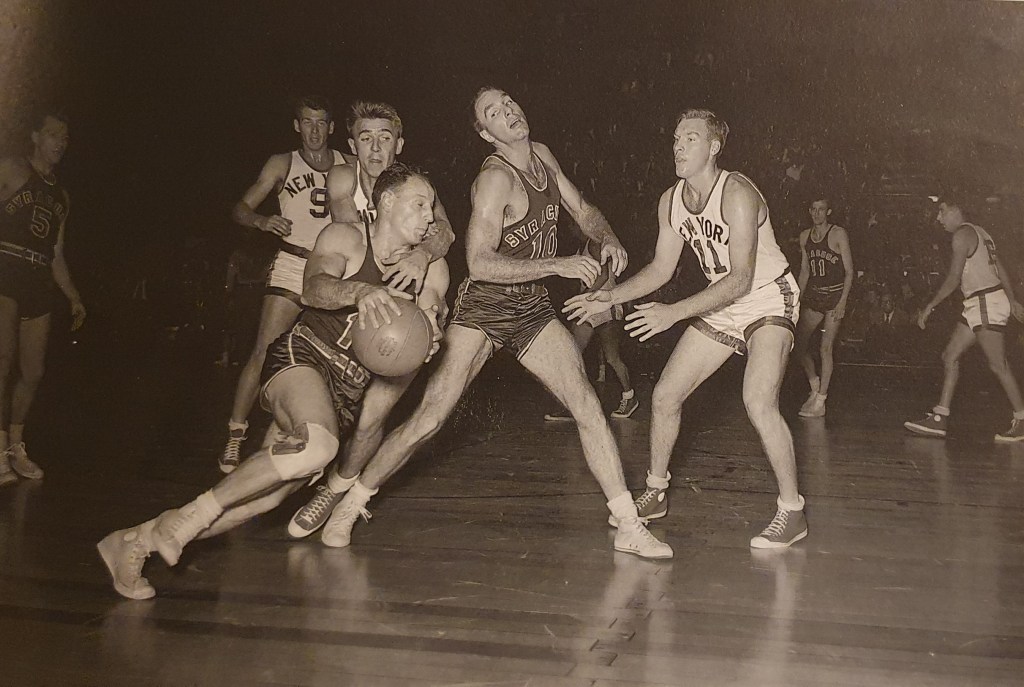

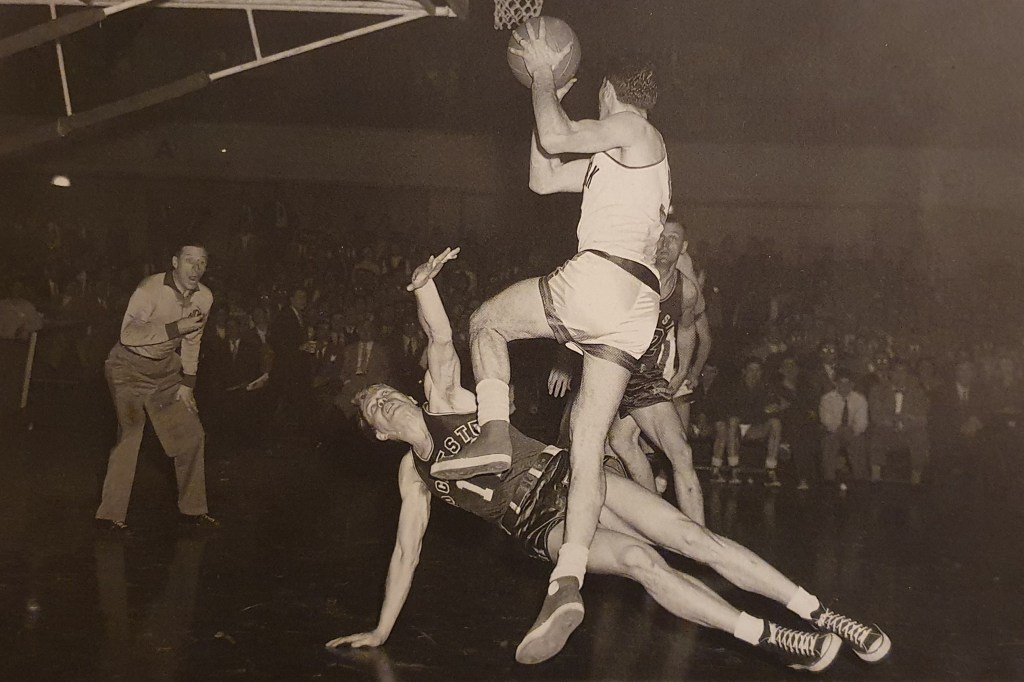

Rules That Favored the Defense and Games That Often Ended in Fights

Let us be clear. Basketball in the 1940s and 1950s was defined far more by physical brutality than by any kind of aerial game. With the George Mikan revolution, which demonstrated beyond doubt the tactical advantage of having a tall, mobile, skilled big man capable of blocking shots and keeping opponents out of rebounding position, physical play near the basket became the dominant style.

Hard fouls were a constant part of the game. There were no rules limiting the number of team fouls per quarter. When a foul was committed on a player not in the act of shooting, only a single free throw was awarded. As a result, defenses could avoid giving up two easy points at the rim by conceding just one attempt from the line.

The game was built around passing and collective movement. Very little dribbling, very little space, very few open shots, and inevitably a great deal of contact. It is also important to remember that the 24 second shot clock did not appear until October 1954. Before its introduction, teams holding a lead had every incentive to stall, slow the game down, and send opponents to the free throw line. The result could be truly grotesque displays, such as a March 1954 game between the Knicks and Celtics that lasted more than three hours and featured 119 free throws.

In the book From Set Shot to Slam Dunk, Bill Sharman, the Celtics’ star guard from 1951 to 1961 and one of the best shooters of his generation, recalled:

“With less running and fewer team movements, referees allowed much more pushing, grabbing, elbowing, and rough hand checking. I think that’s why there were so many fights in the early years.“

Mikan thrived during this period. After a defensive rebound, he would outlet the ball to Slater Martin, who would bring it up at a crawl, waiting for his center to establish position in the paint. A lob pass, two points for Big Mike. Simple and unstoppable.

One night in March 1954, an attempt was made to raise the height of the basket by more than 50 centimeters, setting it at 3.60 meters during a Lakers road game against the Milwaukee Hawks, in the hope of slowing down Mikan and Clyde Lovellette. The result was exactly the opposite. While the overall shooting in the game was dreadful, under 29 percent, Minneapolis still escaped with a narrow road win. The experiment was abandoned immediately and never repeated, far less effective than the widening of the lane in 1951, a rule already designed at the time to curb Mikan’s dominance.

Zero comfort in the 1950s NBA

Sharman again, describing the hellish conditions of the 1950s:

“Most of the buildings and basketball arenas were very old and run down, which made playing extremely difficult. In Baltimore, we played on an ice rink. In Syracuse, we played in an old building on the fairgrounds, with a leaking roof, warped floors, and very little heat. There were very few basketball arenas like there are today, and most of them were poorly lit, with all kinds of different and inadequate floors, bad temperatures. Many were used for hockey, and we played directly over the ice, with no insulation other than the basketball floor itself. With frozen hands and fingers, it certainly didn’t help ball handling or shooting. Add to that the fact that basketballs were not molded until the late 1950s and were often misshapen. It made dribbling and shooting much more difficult.”

Uniforms did not help either. Jerseys were made of poor quality cotton, sometimes wool, with a rough texture that trapped sweat. Shorts were often satin. Teams had a limited number of uniforms for the entire season, prioritizing durability over comfort. It would not be until the 1960s that players benefited from polyester and nylon jerseys.

For Charley Rosen, author of The First Tip-Off, these anti athletic uniforms were one of the reasons behind poor shooting percentages:

“The uniforms were tight, but those wool textured jerseys absorbed sweat like a sponge. By the end of the game, they could weigh over a kilogram. The added weight and discomfort restricted players’ freedom of movement.“

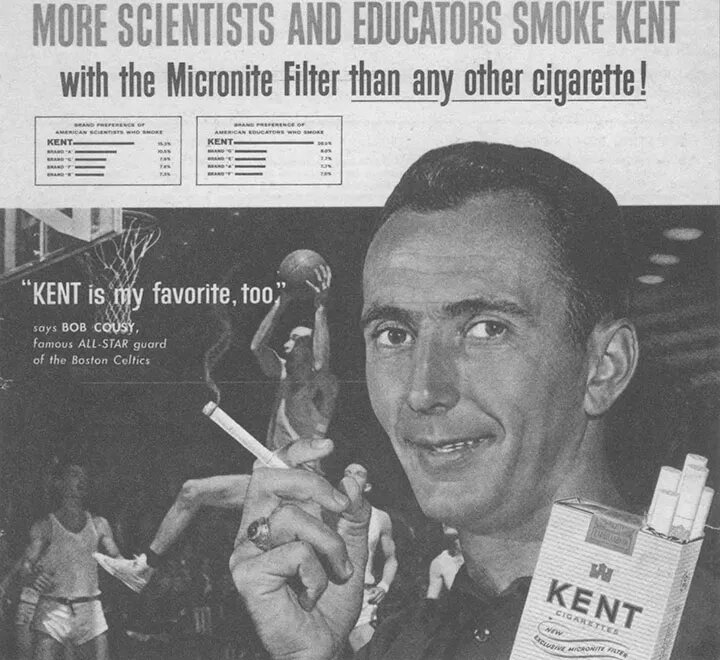

There are a few obvious points worth mentioning more briefly. Beyond warped floors, rims attached directly to the backboard, balls that were not always round and often made of poor leather, with inflation valves that could stick out, and Chuck Taylor All Stars that were stiff as boards, arenas were filled with cigarette smoke from spectators. Madison Square Garden in its third version, MSG III from 1925 to 1968, was particularly notorious in the 1940s and 1950s for its toxic combination of smoke and poor lighting. From certain angles, the basket was simply impossible to see.

Some other absurdities regarding arena conditions in the 1950s:

At the State Fair Coliseum in Syracuse, the cables holding the backboards ran through the stands, and spectators could pull on them to move the basket when the opposing team attempted a shot.

At Edgerton Park Sports Arena in Rochester, swinging entrance doors were placed so close to the basket that players who slipped after a fall could slide straight through them and end up outside in the snow.

And then there was the Keil Auditorium in St. Louis. Half of the building, normally a conference space, had a standard basketball floor, while the other half was a theater whose stage was separated from the court by a shared wall. It was not uncommon for a concert or ballet to take place at the same time as a game, and distracted players exiting the locker room could walk through the wrong door, much to the dismay of an orchestra or a soprano mid aria.

A chaotic playing environment in a young, underfunded NBA, hardly conducive to the development of a refined game or consistent shooting.

The Perfect Counterexample: The Free Throw as an Invariant

The free throw is perhaps the shot that allows the easiest comparison across eras. While advanced statistics quickly reach their limits when comparing players from different periods, how do you account for frozen floors, misshapen balls, or visibility obscured by cigarette smoke, the free throw remains a stationary, uncontested shot. The original distance of 4.57 meters has remained unchanged.

As a pure shooting exercise, one might reasonably expect early NBA players to post free throw percentages well below modern standards, given their lack of early training. Most pioneers of the league did not grow up practicing basketball as children or teenagers, unlike later generations.

With a far higher volume than today, nearly 35 free throws attempted per game on average compared to around 27 in the 1990s and even fewer in the modern NBA, it may be surprising to see that the 1950s produced an average free throw percentage of 73 percent. That figure sits squarely within modern norms. It is even higher than the 1960s at 72.5 percent and not far from more recent decades, 74.6 percent in the 1990s and 76 percent in the 2010s.

Here, the comparison cannot be distorted by external rule factors. While ball quality was certainly inferior to what would come later, the height of the basket, the circumference of the rim, and the distance from the line remained unchanged. In this case, there is only the shooter and his accuracy, alone at the line, with no defender to contend with.

Bob Cousy offers a useful example. The Celtics guard finished his career with a field goal percentage of 37.5 percent. Yet Cousy was an excellent free throw shooter in his time, averaging 80 percent over thirteen seasons. The issue was not shooting technique, but the environment in which shots were taken, combined with shot selection. This was especially true for Cousy, who had a habit of attempting difficult, improvised shots, much to the frustration of Red Auerbach.

In conclusion, it is clear that the pioneers of modern basketball were far from incompetent. On the contrary, in conditions that today would likely trigger an immediate work stoppage, and under some of the most restrictive rules imaginable, players of the 1950s NBA laid the foundation for the celebrated 1960s, in a league that had neither money nor infrastructure.

Leave a comment