A portrait of greatness shaped by doubt, discipline, and inner conflict

“I played with an angry, emotional chip on my shoulder and a hole in my heart. My worst personal trait, by far, is that I expect everyone to care as much as I do, about everything, and it is both terrible and unfair. My life has been about trying to figure out my limitations and I know them quite well. Once you find out what they are, it really gives you a chance to find your niche.”

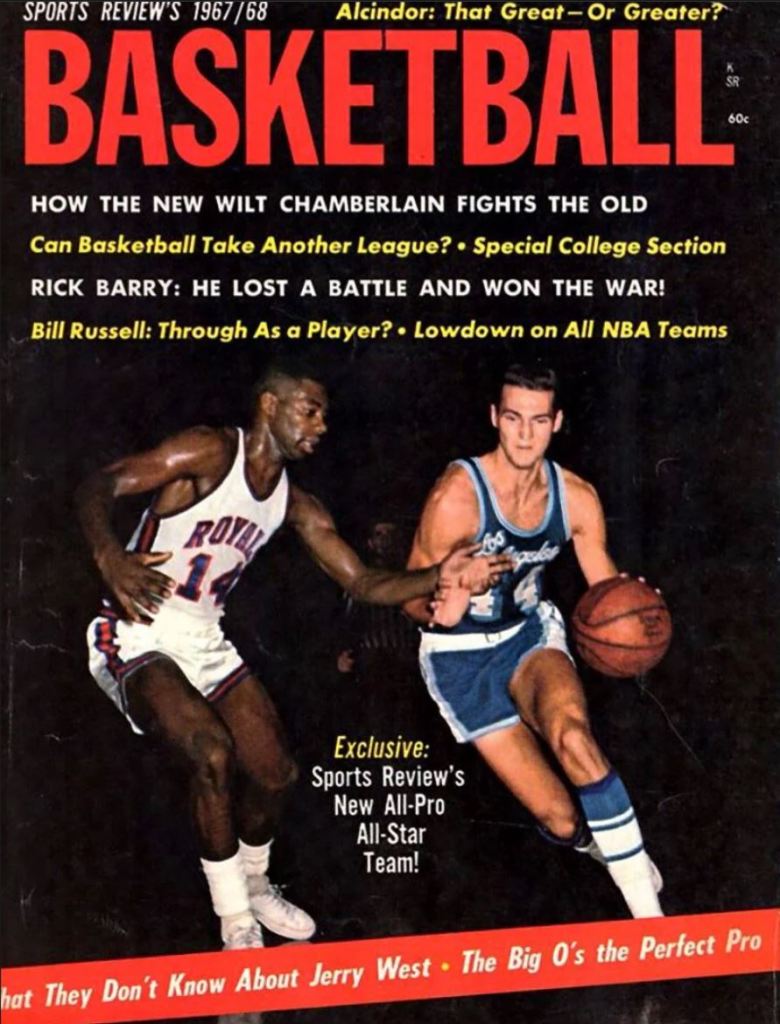

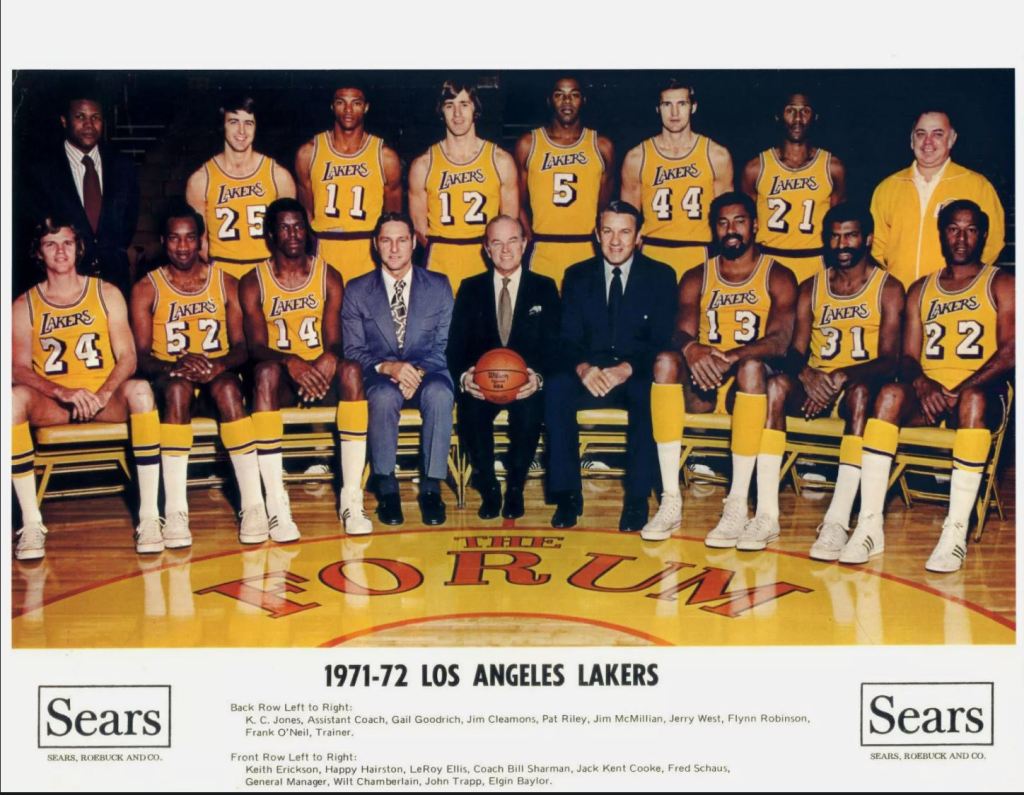

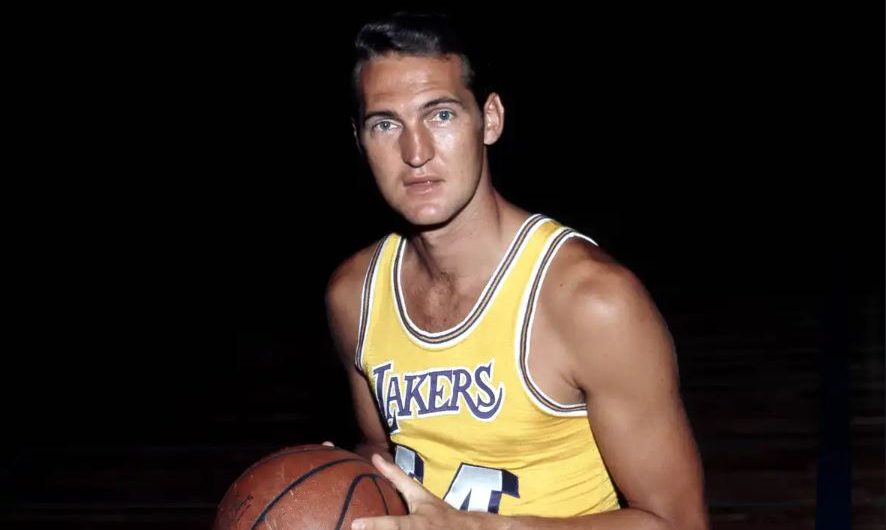

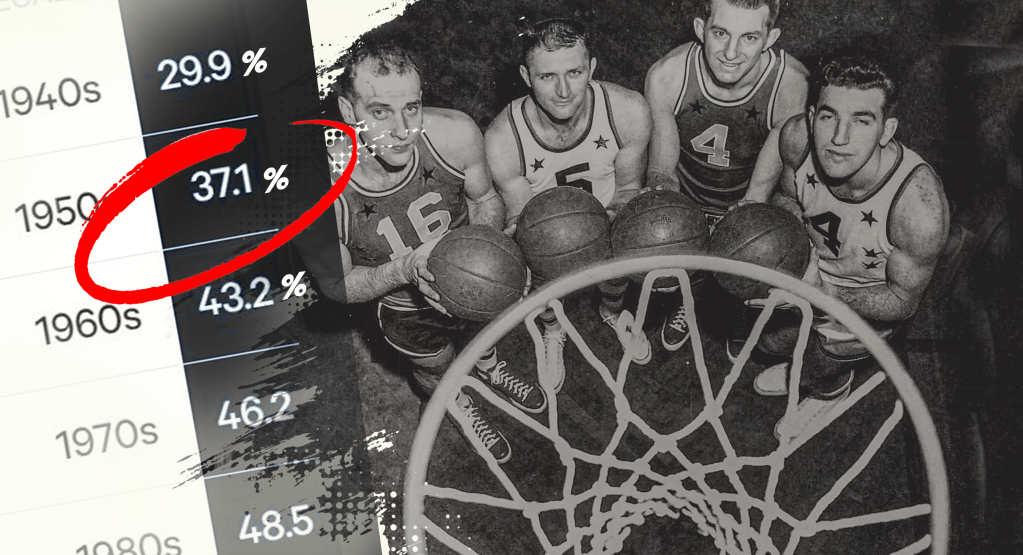

Any NBA fan knows Jerry West, at least in broad strokes. The Logo, Mr. Clutch, the Lakers Celtics rivalry of the 1960s, the 69 win season and the 1972 title, 14 straight All Star selections, 12 All NBA honors, 5 All Defensive teams, a three time Hall of Fame induction, a unique case, not to mention nearly a quarter century as an executive, with the success we all know. Much less familiar is the man away from the uniform.

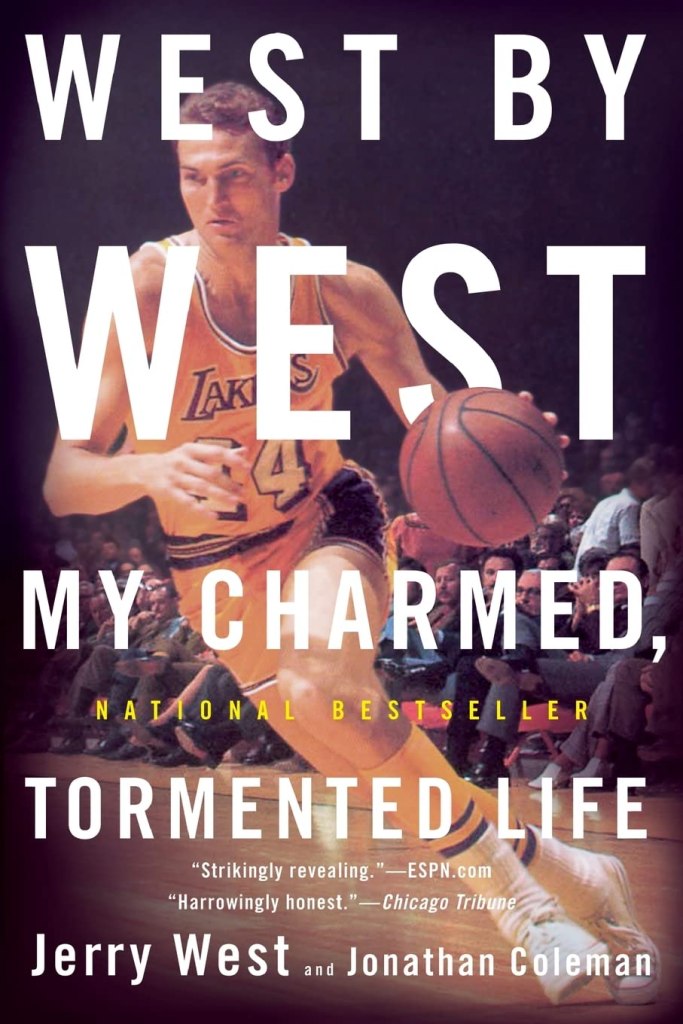

His autobiography, published in 2011 and co written with Jonathan Coleman, was ranked by the American press among the essential reads. I came to it late, and quickly realized this is not a standard autobiography. The subtitle, “My Charmed, Tormented Life“, is not exaggerated in the slightest.

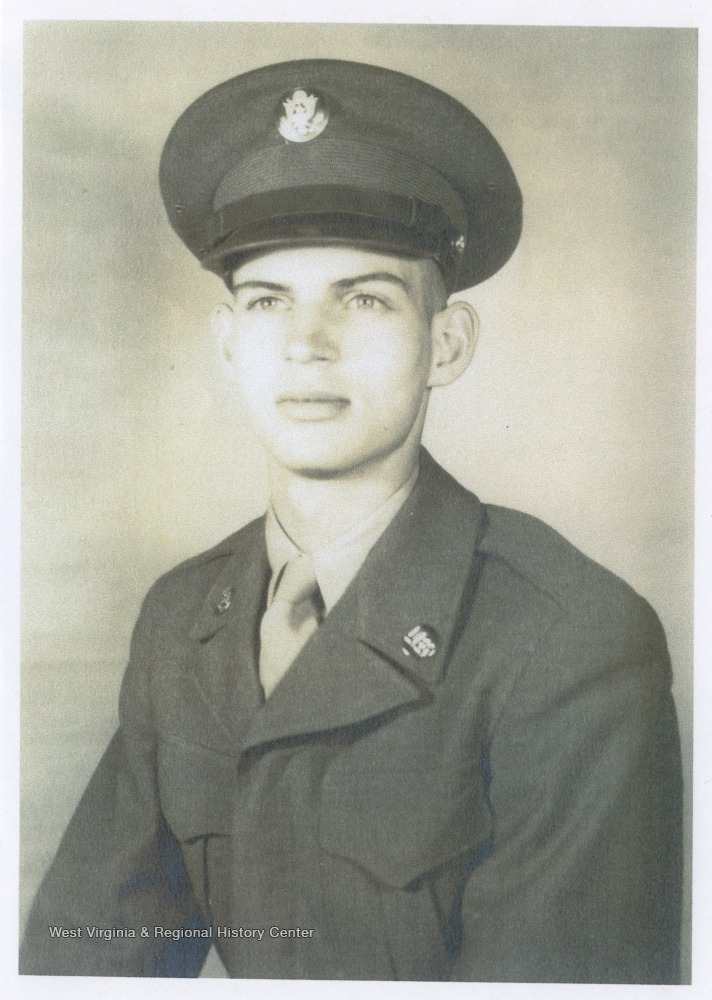

Jerry West was not just a great player. He was an elite figure, a tormented soul, neurotic, fully aware of how singular his personality was, constantly brushing up against depression. His childhood was anxious: isolated, not eating enough, he tragically lost his older brother in 1951 during the Korean War, and endured the violence of a philandering father. He spent several nights with a loaded rifle under the bed, ready to defend himself if his father went too far.

Jerry West has everything to be adored, yet he spends most of his time explaining why he does not like himself. Away from the court, his life revolves around staying as far from people as possible. Reading books about war or comparative mythology. Watching wildlife documentaries. This is worlds away from the packaged autobiography, a box of warm memories and colorful anecdotes. Here, the mood is heavy. West is haunted by war, never feels joy, always on edge, hovering right at the waterline of depression. Clear eyed, he calls himself a fatalist:

“In terms of the neurotic anguish Campbell writes about (Joseph Campbell, the American mythologist), I don’t think neurotic applies to me, I really don’t. Superstitious, yes. Odd, no doubt. Experiences and suffers anguish, most definitely. But neurotic? No. I’m not Woody Allen, for Christ’s sake.”

A third of the book in, you have barely read a few lines about basketball, and you understand that West is not the average person you might meet on the street corner. The man is deep, subtle, unsettling. The exact opposite of Charles Oakley and his bland autobiography, which I might talk about here one day if I can bring myself to. The book also stands in total contrast to the sleepy feel of Roland Lazenby’s work, who has written on West but also Jordan, Magic, and Kobe. You come away shaken.

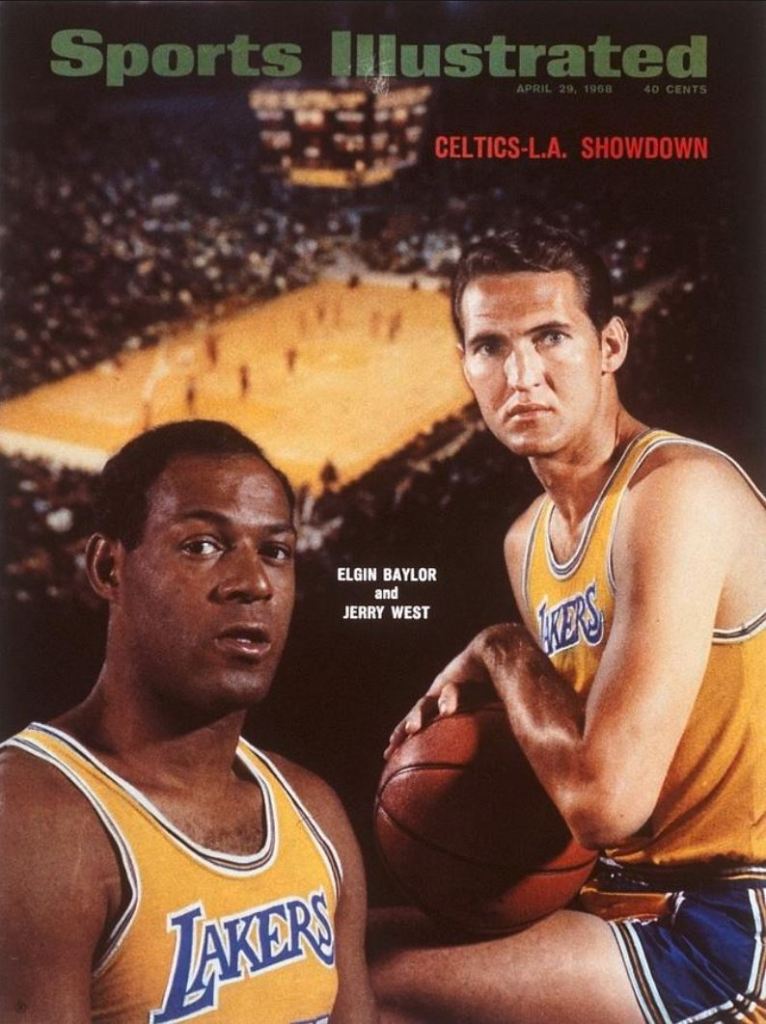

Thankfully, it does talk basketball. But the strictly “player” portion, the 1959 NCAA Final Four with West Virginia, the gold medal at the 1960 Rome Olympics, then his fourteen seasons with the Lakers, does not take up as much space as you might expect. Still, there are several strong stretches, especially the pages about his relationship with teammate and friend Elgin Baylor, “the first player to really play in the air, the forerunner to Julius Erving and Michael Jordan”, and the six Finals losses to the Celtics in the 1960s. He also revisits his shifting on court roles, first as an ultimate scorer, then more of a playmaker, the league’s assists leader during the 1972 title season. He returns at length to his conflict with Jack Kent Cooke, the Lakers owner from 1965 on, who does not come out looking good in this book. One chapter focuses on Wilt Chamberlain, where West punctures the myth of the man with a thousand conquests and instead describes someone deeply solitary.

On his playing career:

“I was relieved to have won one championship, but had hoped for more, much more. That’s the raw, unvarnished truth. That feeling of having been a prince far more than a king continues to gnaw at me. I dislike the color green. I rarely go to Boston. Is this, any of this, in any way rational? No, of course it isn’t, but then again, neither am I.”

On court details and anecdotes help balance the emotional weight of the introspective sections. He recounts the hell Pat Riley put him through in practice:

“His main job on the Lakers, as outlined by Fred Schaus, head coach of the Lakers from 1960 to 1967 and former Pistons player in the fifties, was to beat the hell out of me in practice (but not kill me, as he often tried to do).”

On his brief stint as a head coach, three seasons with the Lakers from 1976 to 1979, West admits he was too young and far too demanding for the job. The results were still respectable, three playoff runs in three seasons, because he took over a team that had missed the playoffs for two years. As soon as he was named head coach, he chose Jack McCloskey as his defensive assistant without hesitation, and especially Stan Albeck for offense, because, paradoxically, West had no idea how to structure his team’s offense, despite being a genius with the ball in his hands as a player. Three seasons without a breakthrough for Lakers trying to build around Kareem Abdul Jabbar, a middling team that had no idea salvation would arrive a few months later with the spark of Magic Johnson.

“I was so hard on the players, particularly verbally, so hard. To this day, I feel bad about the horrible way I treated them (especially Brad Davis and Norm Nixon). Whenever I think about Kareem Abdul Jabbar, I regret the way I dealt with him as a coach. I feel bad that I said he didn’t play hard enough. When I think about players, I primarily think about their basketball IQs. I think about what kind of play a player will make when the game is on the line. About whether he will be more precise, be less likely to make mistakes.”

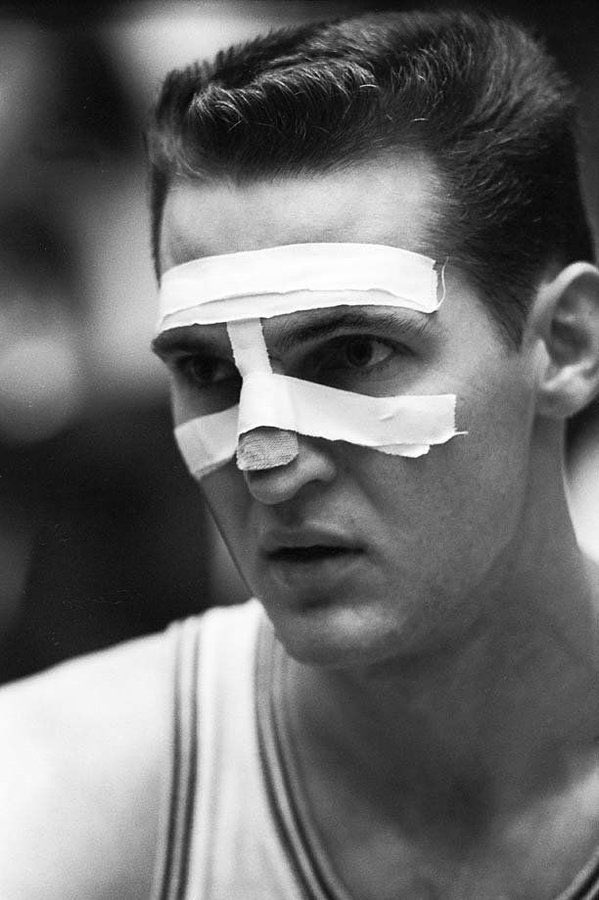

If he is remembered as one of the most elegant players in the game’s history, it should not be forgotten that he was a thorn on the court. Near the end of the book, he lists all the injuries he suffered over his career. It takes up three full pages. He broke his nose nine times, yes, nine.

Being soft on a basketball court was one of the things he could not stand, and one of the frequent criticisms he leveled at certain players when he was a GM. Especially at the young James Worthy, excellent from the start. An attitude that felt too nonchalant or too gentle could affect whether a contract extension happened. Yet it was West himself who fought with everything he had in 1986, even though the deal had been set up behind his back by Magic and Jerry Buss, the Lakers owner from 1979 on, to stop that same Worthy from being traded to the Pistons for draft rights to Roy Tarpley and Mark Aguirre of the Mavericks, a close friend of Magic. By everyone’s admission, through several testimonies included in the book, if there was one thing West could not stand it was plotting, flattery, and backroom games. With Magic as a player and Buss as president, you can imagine how many situations he had to defuse.

We also learn, still on Worthy, that he was Panathinaikos’s top target in 1994, but after he turned down the offer and chose to retire, the Greeks “settled” for Dominique Wilkins.

I used James Worthy as one example, but West develops a whole range of stories, anecdotes, and conflicts involving players from the Showtime era, Byron Scott, Magic of course, Kurt Rambis, and many others.

The part of the book about his executive life is the most entertaining to me. West is talkative, more direct, and above all he owns every decision, explaining many of them, coaching hires, trades, draft choices, including taking James Worthy in 1982 instead of Dominique Wilkins or Terry Cummings, which ran against the conventional thinking at the time, since Wilkins was a much better scorer and Cummings a much better rebounder and defender.

An entire chapter is devoted to the summer of 1996, the headache recruitment of Shaquille O’Neal and the draft of Kobe Bryant. He goes back over the difficult trades of Eddie Jones and Nick Van Exel, the heaviness of Glen Rice, and his relationship, initially excellent, with owner Jerry Buss, which gradually frayed. He also discusses Phil Jackson, complicated from the start, which contributed to the end of West’s Lakers tenure right after the 2000 title. There are strong pages on Chick Hearn, the first to call him Mr. Clutch, Mitch Kupchak, and many others. Some of this overlaps with what we already covered in the Jeff Pearlman book article.

Then comes Memphis, where he believes he had four excellent years out of his five with the Grizzlies. Executive of the Year in 2004, and Hubie Brown as Coach of the Year in his final season on the bench:

“I made a number of mistakes in Memphis: drafting Drew Gooden instead of Amar’e Stoudemire was one; signing Brian Cardinal for the midlevel exception was another but I was fortunate enough to bring to the team its second future star in Rudy Gay. Pau Gasol had been Rookie of the Year in 2002, the year before I arrived, but he suffered a major injury that prevented him from playing for the Grizzlies in the same consistent, passionate way he had played for Spain. That meant trading one of my favorite players on the Grizzlies, Shane Battier, who also did so many good things in the community, which was not an easy thing to do. Shane was a very solid player and a great defender but he was not a star, and a team needs at least one, and ideally two. It may not have been a popular move but it was the right decision.”

To close, I will bring back this quote I had noted, a line Jerry tells from a debate with one of his sons in the car about which NBA player was the most underrated:

“John Stockton was perhaps the most underappreciated player ever to play the game. And that as much as I admired Larry Bird as both a player and a competitor, I wasn’t sure Rick Barry hadn’t been just as great. Because Rick seemed to be so disliked personally, I don’t think he got the acclaim he deserved professionally.”

Jerry West died in June 2024 at the venerable age of 86, leaving behind a crucial testimony for anyone trying to understand him. The story of a champion who, for all that, never knew happiness or the simple pleasure of the game, eaten up by a dull guilt and an almost pathological level of inner demand. A complex, tortured man, and yet a commanding figure, as his quarter century as an executive proved. The basketball sections help lighten many stretches of an embraced and disorienting fatalism when you first enter the book.

The great discovery here is the kind of man Jerry West was. In another era, I can easily picture him as an army general, a kind of Marcus Aurelius, or one of those sleepless commanders driven by an inner force. An elite man who never truly enjoyed his obvious superiority, a strategist with something slightly unhinged, who only feels at home in tragedy. An essential book.

Leave a comment