A builder of modern European basketball, from Belgrade to Olympic gold

Born in 1929 in Dragutinovo, renamed Novo Miloševo in 1946, Ranko was, like the vast majority of his peers, a player before becoming a coach. He quickly understood, however, that his contribution on the court would be limited. So while still a player with KK Radnički in Belgrade, only 25 years old, he took over the team, but from the bench. Under his authority was another Yugoslav basketball legend, Dušan Ivković. After a few years of service at Radnički, he became an assistant coach to Aleksandar Nikolić with the national team in the late 1950s. As an assistant, Žeravica took part in Yugoslavia’s first major international breakthrough, the silver medal at EuroBasket 1961 in Belgrade, following a 53–60 loss to the USSR in the final. He later became a tireless club coach, with a trophy case that was admittedly thin across fifty years, but it is his fertile run at the head of the national team that stands out.

Here are a few key points from Ranko Žeravica’s career.

1966: Chile and The Phantom Medal

In his first experience as the head coach of Yugoslavia, Žeravica quickly won a medal, rarely celebrated, but one he took pride in. It came from a world championship that was never officially recognized, held in April 1966. The FIBA World Championship was initially scheduled for Montevideo, Uruguay, but due to political instability and runaway inflation, Uruguay asked FIBA to postpone the tournament to 1967, a request the governing body accepted. To compensate the teams already deep into preparation, an unofficial competition was organized instead.

After the first phase, the twelve best teams, along with the host nation Chile, advanced to the final tournament in Santiago. Yugoslavia finished first ahead of the USSR and the United States, with Radivoj Korać as the leading scorer, followed by Chilean Juan Guillermo Thompson and Spanish naturalized Clifford Luyk. The victory marked Žeravica’s first medal as head coach, even if it would never be officially recognized.

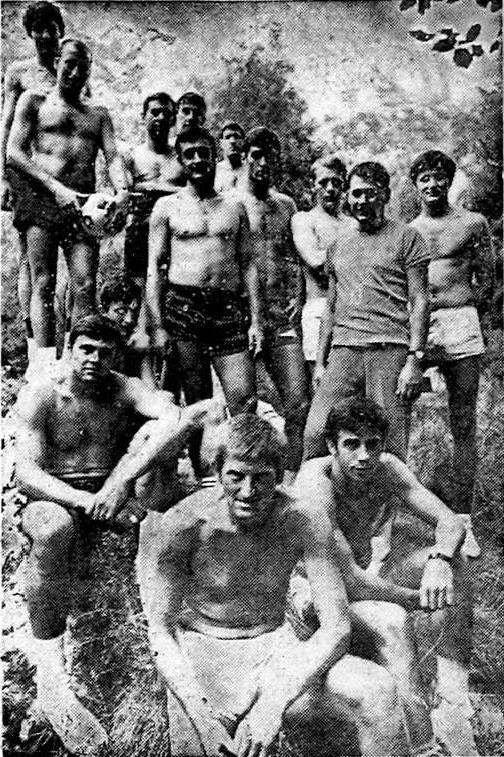

For Yugoslavia’s third Olympic appearance, after Rome and Tokyo, the team was far from being a favorite. A year earlier, a modest ninth place at the European Championship in Helsinki was considered a total fiasco, coming after silver at EuroBasket 1965 in Moscow and gold at the unofficial world championship in Chile in 1966. A generational shift played a role, and despite the criticism, Ranko fully embraced the choice to select young, promising players who were not yet ready for the very highest level.

The team had changed dramatically compared to Tokyo 1964. In place of Sija Nikolić, Nece Đurić, Pino Đerđa, Rica Gordić, Kovačić, and Džimi Petričević, the players who had made Yugoslav basketball famous at the start of the decade, came the young and promising Krešimir Ćosić, Damir Šolman, and Miško Čermak, who would later coach Antibes and Stade Français. Five selected players were only 19 years old. Ranko knew them well, having coached them as juniors. After a strong qualification tournament in Sofia, three players were named to the tournament’s best five, Ćosić, Daneu, and Čermak, alongside France’s Jean-Pierre Staelens and Finland’s Limo.

As part of the preparation, he took the team into the mountains of Macedonia so the players could get used to altitude, and scheduled practices at three in the morning to help them adjust to local time. A few changes followed, Skansi, the future coach of Benetton Treviso, later beaten by CSP Limoges in the 1993 European Cup final, and Ražnatović replacing Pazmanj and Kapičić, and then came an opening win, 96–85 over Panama, despite 28 points from guard Peralta Davis. More wins followed, 93–72 over Puerto Rico, then 84–65 over Senegal, with 27 points from Cvetković.

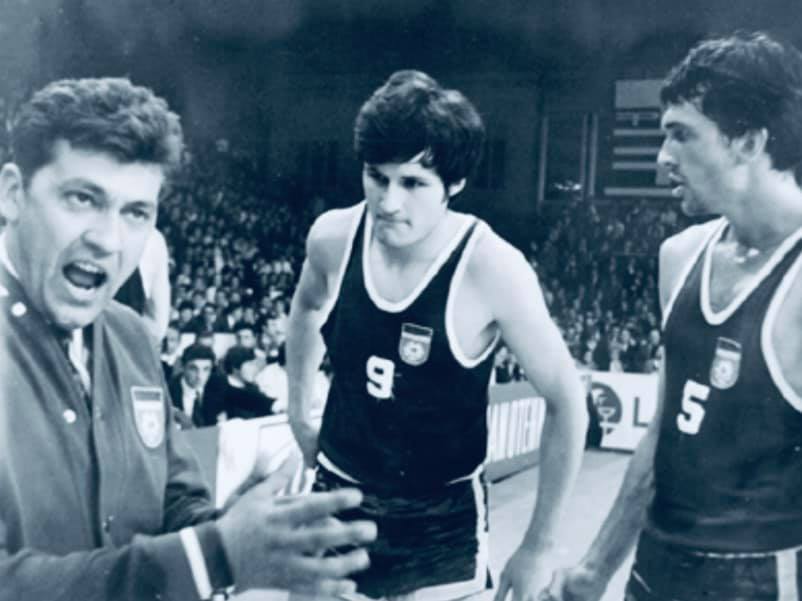

The main test was Team USA, and unsurprisingly it ended in a 73–58 loss, led by Spencer Haywood and Jo Jo White, who scored 24 points. The group stage ended on a high note with three wins against Spain, Italy, and the Philippines. In the semifinal against the USSR, Žeravica’s team entered as an underdog. But in front of 22,000 spectators in Mexico City, Yugoslavia earned a place in the final, beating the Soviets 63–62, a first.

Against the Americans, there was no miracle. It was a respectable 65–50 loss, only three points behind at halftime. But after the break, the college players unleashed a brutal 17–0 run to end the suspense. Still, it was better than the 104–42 beating in the 1960 semifinal in Rome, and more importantly it was a final that brought Yugoslavia silver, the first Olympic medal in the nation’s history.

For the first world championship held in Europe, Yugoslavia hosted in Ljubljana. Since the first World Championship in 1950 in Buenos Aires, every edition had taken place in South America. In 1970, twelve teams were divided into three groups, Sarajevo, Split, and Karlovac, and Yugoslavia, as the host, advanced directly to the final round in Ljubljana. An advantageous format.

After winning silver at EuroBasket 1969, Žeravica and his players had a real opportunity. In the opening round, they survived a difficult game against Italy, winning 66–63 under the eyes of Tito, watching from the presidential box at Tivoli Hall. Ćosić posted 29 points and 22 rebounds. Next came Brazil, a 80–55 blowout in favor of the hosts, even though that same Brazilian team had recently beaten the USSR. Wins followed against Czechoslovakia and Uruguay.

In the sixth and next-to-last game of the tournament, Yugoslavia faced the USA. Win, and gold was secured. On the American side, the young Bill Walton and Tal Brody, the future icon of Maccabi Tel Aviv, formed the standout duo. The game was close, but Yugoslavia stayed in front throughout. A 70–63 win, the first gold medal for the host nation. In the final game, which was meaningless in the standings, they lost 87–72 to the Soviets, who finished third behind Brazil. The celebration was total, all the more so as basketball was beginning to be broadcast on television, reaching larger audiences. Sadly, only three days after the gold medal, center Trajko Rajković died from a heart defect.

1974–1976: The Barcelona Experience

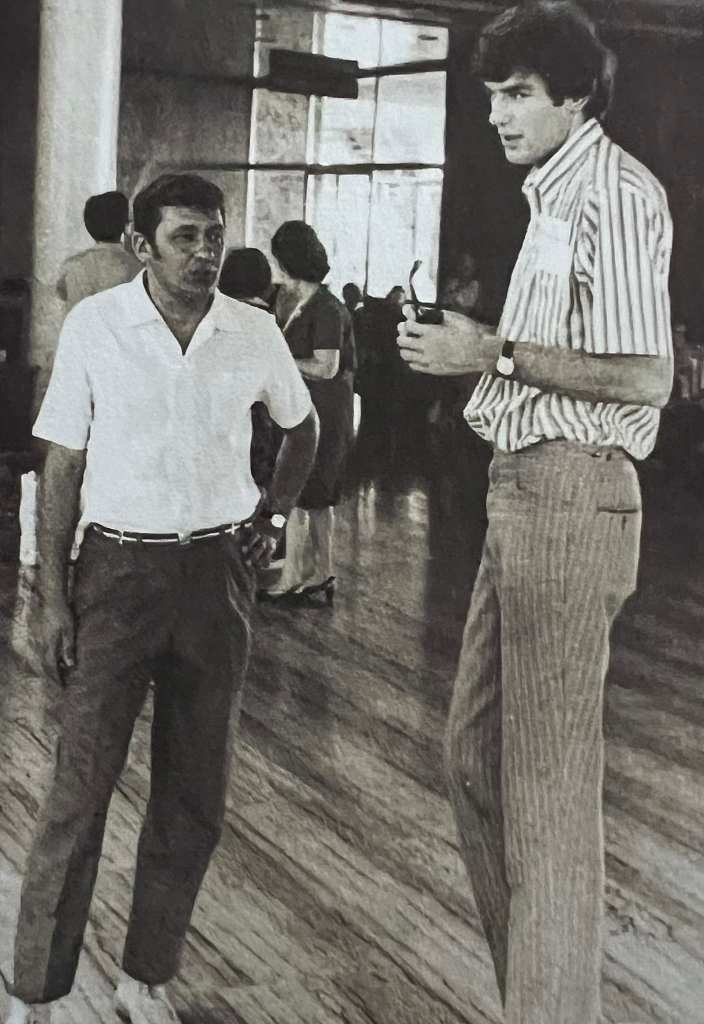

In 1974, he was authorized to work abroad by Interior Minister Slavko Zečević, who had also been his president at Partizan, as was common at the time. Ranko arrived in Barcelona in May 1974 with a two-year permit.

Eduardo Portela, who would later become president of the ULEB, was a key figure at FC Barcelona and decided to hire him. Far from the modern powerhouse, Barcelona’s basketball section in the 1970s was not a model of professionalism. On arrival, Ranko felt like he was coaching handball players, training only two or three times a week.

The experience started badly. His apartment was burglarized. His arrival made waves, and the thieves were looking for the money from his contract. Then his best player, The Black Panther, the American Charles Thomas, presumed dead for forty years and found alive in 2021, an incredible story, broke his leg against Real Madrid. Then his wife Zaga broke her hip in a domestic accident.

But the Yugoslav’s harsh and professional methods soon paid off, as Eduardo Portela recalled:

“He was a great man and a great coach. Barcelona owes him a great deal, because he changed our way of seeing basketball. He opened new horizons in our work with young players. His reflections on the game were a great revelation for all of us. He left a deep mark and a great number of friends.“

Among the young players, he spotted a left-handed guard, a bit frail but quick, and made him his point guard: Nacho Solozábal, who would become one of Spain’s most influential guards, winning two silver medals, at EuroBasket 1983 and the 1984 Olympics.

Forward Manolo Flores and the legendary Juan Antonio San Epifanio were the other two locals Ranko promoted to the first team. The Dominican, five-time Spanish champion Chicho Sibilio, naturalized Spanish and spotted in a friendly match, was signed by Ranko in 1976, as was Juan Domingo de la Cruz, Argentine-born.

In two seasons, they won no trophies. Still, FC Barcelona credited the Slavic coach with modernizing the club’s basketball section and contributed financially to Zaga’s museum project dedicated to her late husband in his hometown of Novo Miloševo.

1977–1978: A Wildly Offensive Partizan

In 1978, leading Partizan Belgrade, Ranko and his team produced a memorable season. Over the full campaign, Partizan averaged 110.5 points per game. Staggering.

After two years in Barcelona, he returned to Partizan, led by Dragan Kicanović and Dražen Dalipagić, both at the peak of their powers. The centerpiece was an unbelievable Korać Cup final against Bosna Sarajevo, decided in overtime, a 117–110 win, with 48 points from Dalipagić and 33 from Kicanović. For Sarajevo, Mirza Delibašić scored 32 and Žarko Varajić added 22. A few days later in Belgrade, Bosna won 109–102 in a decisive league game, despite another 48 from Dalipagić, and captured the national title, sending them to the next season’s EuroLeague, which they would win in 1978–79 against Italy’s Varese.

Partizan finished second, and Ranko would not win a national league title with a club team until 1996. The two top scorers in the league were, of course, Dalipagić at 34.4 points per game and Kicanović at 33.7. At the end of the season, Ranko left Partizan. The club won its second league title in 1979 under Dušan Ivković.

Ranko experienced heart problems for the first time during the 1978–79 season. Doctors advised him to stay away from the bench for a while, but rest did not suit him. He chose to coach KK Pula, a modest regional team, far from the pressure of the national elite.

At the same time, he became an adviser to Argentina’s national team. Not physically on the bench, but an ideologue for the project. Argentina qualified for the Moscow Olympics, even though they ultimately did not attend because of the boycott, while Ranko accepted an invitation from the Yugoslav federation to return to the national team bench, after a 1979 European Championship that was considered disappointing despite the bronze medal in Moscow.

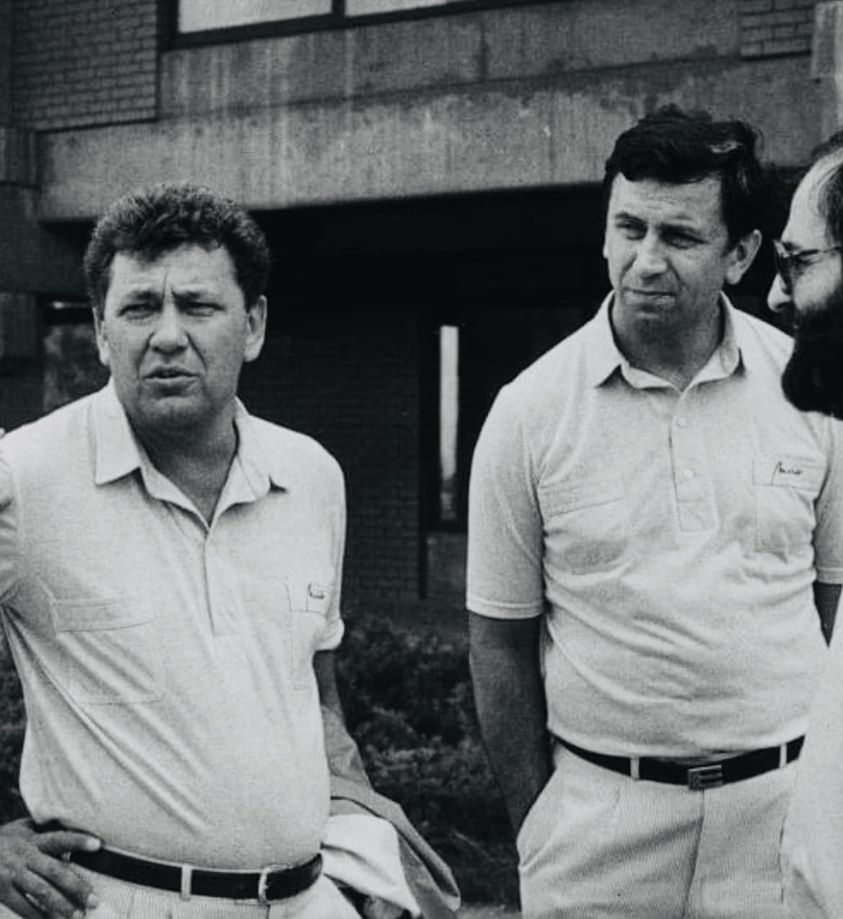

1980: Olympic Gold

Between Montreal 1976 and the Moscow Games in 1980, the national team went through three head coaches. In 1976, at the Montreal Olympics, Mirko Novosel won silver against the Americans. Aleksandar Nikolić returned for EuroBasket 1977 in Belgium and the 1978 World Championship in Manila, and both tournaments ended with gold medals. For EuroBasket 1979 in Italy, the team was handed to Petar Skansi, Nikolić’s assistant in Manila. But the bronze medal at EuroBasket 1979 was viewed as a failure, as were the Mediterranean Games in Split, where Yugoslavia lost 74–85 to Greece in the final, and Skansi was not retained for Moscow. The choice fell on the former Žeravica Novosel pairing, which had already worked together in 1971 and 1972.

It is obvious that the absence of the Americans for these Games, due to the boycott following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, was a gift for Spain, the USSR of course, Italy, and Yugoslavia. The American team, the youngest ever assembled, had been intimidating: Mark Aguirre, Rolando Blackman, Sam Bowie, Bill Hanzlik, Alton Lister, Rodney McCray, Isiah Thomas, Michael Brooks, and Buck Williams.

Absent teams are always wrong. Compared to the roster that won the world title in Manila two years earlier, Žeravica made only one change. Peter Vilfan was replaced by Andro Knego. The start of the tournament was idyllic: 104–67 against Senegal, 129–91 against Poland, and the group stage ended with a duel against Spain, a 95–91 win. In the next round, Italy was crushed 102–81, and Cuba fell 112–84. The game was watched by Soviet coach Aleksandr Gomelski, who left the stands after halftime. “I’ve seen everything I needed to see, why should I waste my time.”

The main obstacle was the USSR of Sergei Belov, and Yugoslavia broke the hosts in overtime, 101–91. A hard blow for the Soviets, who had already lost the day before to Italy. For Yugoslavia, the perfect run continued. Two days later came Brazil, led by a young Oscar Schmidt, and the battle was fierce, a 96–95 win. In the final, their third after 1968 and 1976, Yugoslavia entered as the favorite, and it was a repeat against Italy, 86–77, in a fully controlled game. It was the culmination of a team built from the ground up by Ranko Žeravica, arriving in 1980 with key players at the peak of their powers: Krešo Ćosić, 32, Slavnić, 31, Dalipagić, 29, Kicanović, 27.

In the decade that followed the first gold medal, the one at the 1970 World Championship in Ljubljana, everything had been won: three European titles, two world titles, silver at the Montreal Olympics, silver at the World Championship in Puerto Rico, and finally the long-awaited gold in Moscow. In eleven years and eleven tournaments, only the Munich Olympics in 1972 produced no medal. For Žeravica, this Olympic title was his sixth and second-to-last medal with the national team, before bronze at the 1982 World Championship in Colombia, one final round with his country.

Svetislav Pešić, Serbia’s head coach since 2021, on Ranko Žeravica:

“Žeravica, in my opinion, was the most important coach in our basketball. He was the first modern coach in methodology, technique, tactics, and so on. He did more for our basketball than anyone. He took a backpack and traveled a lot, trained physical education teachers in schools, and gave lectures in Croatia, Macedonia and Montenegro.“

In 2015, 85 years old, with heart issues for years, Žeravica died at home in Belgrade. A tireless basketball man, the night before his death he watched three full games with his wife Zaga, a former Yugoslav international and Red Star player who later became a coach herself. Zaga even recalled that it was two EuroLeague games and one NBA game.

In his honor, Belgrade’s Hala, a former Partizan arena, was renamed the Ranko Žeravica Sports Hall, Хала спортова Ранко Жеравица in Serbian. It hosts games for two men’s teams, KK Mega Basket and KK Dynamic, as well as ŽKK Partizan, the women’s Partizan team.

He was inducted into the FIBA Hall of Fame during his lifetime in 2007, the same year as his compatriot Aleksandar Nikolić, considered the father of Yugoslav basketball.

The Ranko Žeravica Sports Hall, in Belgrade

Leave a comment