A role player whose career ended abruptly, and whose life never recovered

Shadow players, obscure and forgotten by everyone, can be found by the dozen in nursing homes. Full lives. Years in the NBA, sometimes with real success, yet today the memory of their very names survives only on the lips of a few aging storytellers, often already balding. Who still remembers Don Buse, Mark Olberding, or Dave Robisch? Between the three of them, they played close to 3,000 games at the top level. Long careers, more than ten seasons, with their share of emotions, glorious and frustrating. And yet nothing stops the erosion of time, and even less the failure of memory, even among the most devoted fans.

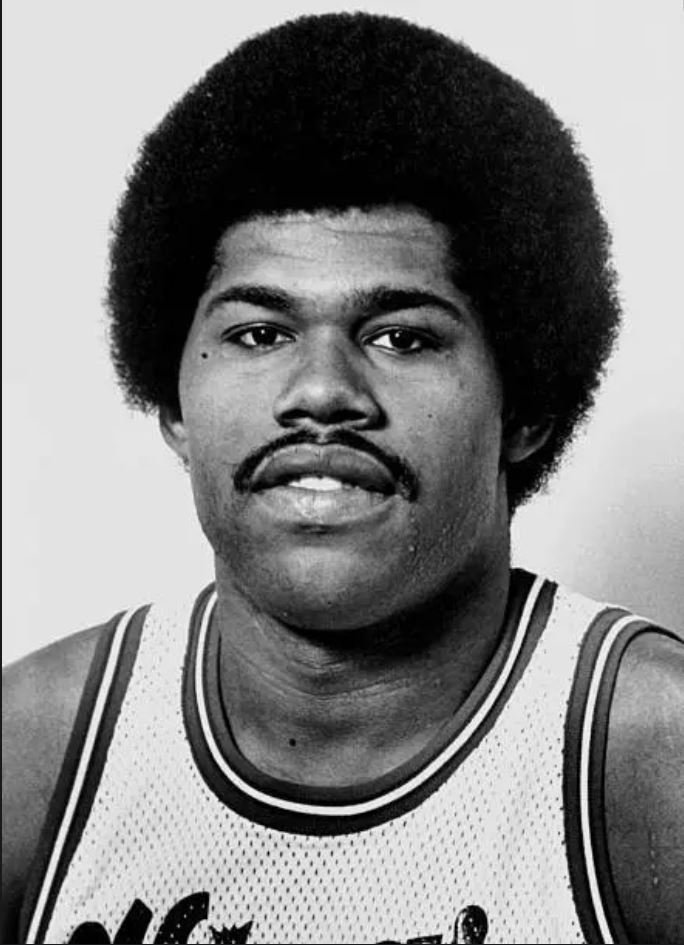

And then there are the forgotten among the forgotten. The ones whose careers, like their lives, stopped abruptly. Bill Robinzine was one of them. In September 1982, after seven NBA seasons, mostly in a Kings uniform, he was found dead in his car in the parking lot of a Kansas City garage. Police ruled it a suicide. Bill Robinzine was 29. No one knew him to have any inclination toward alcohol or drugs, or toward gambling.

An accomplished trumpeter, an inexperienced basketball player

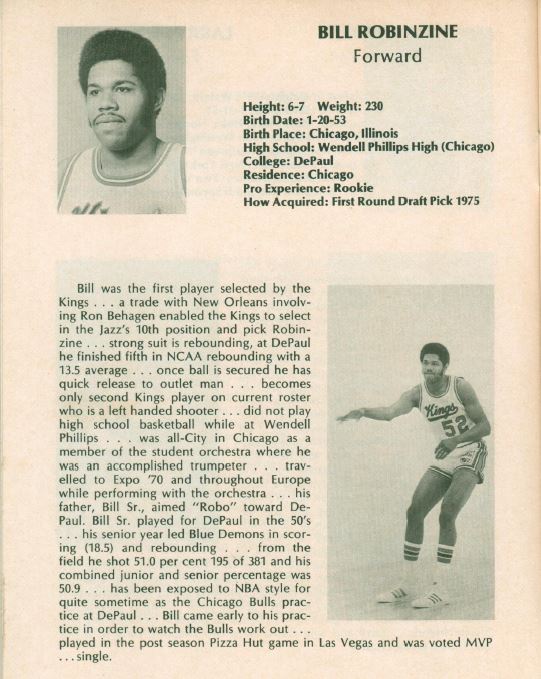

A comet, both because his life was brief, and because even his basketball path was unusual. Despite the right size, a true seven footer, he did not touch a basketball until he was 17, a thick built lefty with a bull neck. A passionate trumpeter, he slowly gave up music for the orange ball only because his friends kept pushing him, helped along by a father who had been a standout college player at DePaul, one of Illinois’s major programs.

A physical detail also pulled him away from his favorite instrument. At 16, a broken tooth from childhood was repaired. During his trumpet learning years, Bill used to blow on the side of that half tooth, and after the dental work, he lost his bearings.

“In my neighborhood, a big guy walking around with a trumpet meant getting jumped. That toughened me up. I didn’t want to play basketball because the guys in my neighborhood had all started young and were much better than me.“

It is incredible to think that only four years later, he was drafted in the first round by the Kansas City Kings, with a solid contract, a little over half a million dollars over four years.

A rapid rise at DePaul, followed by a first round NBA draft

The Chicago native improved day after day, to the point that he joined local school DePaul for three years, including one alongside Dave Corzine, the future Bulls center. Coached by a local institution, the unmovable Ray Meyer, Blue Demons head coach from 1942 to 1984, and the man who had coached Bill Sr., Robinzine’s father, Bill Robinzine gradually emerged. No NCAA tournament appearances despite winning records, but impressive individual numbers for this undersized power forward, built like a heavy French armoire: over 19 points and 11 rebounds a game in his senior year.

Enough to punch his ticket to the 1975 NBA Draft, where he became Kansas City’s first pick at number ten overall. A class considered disappointing, Dave Myers, Marvin Webster, Lionel Hollins, Rich Kelley, yet also the class of David Thompson, Alvin Adams, 1976 Rookie of the Year, World B. Free, Dan Roundfield, Gus Williams, and Jellybean Bryant, Kobe’s father.

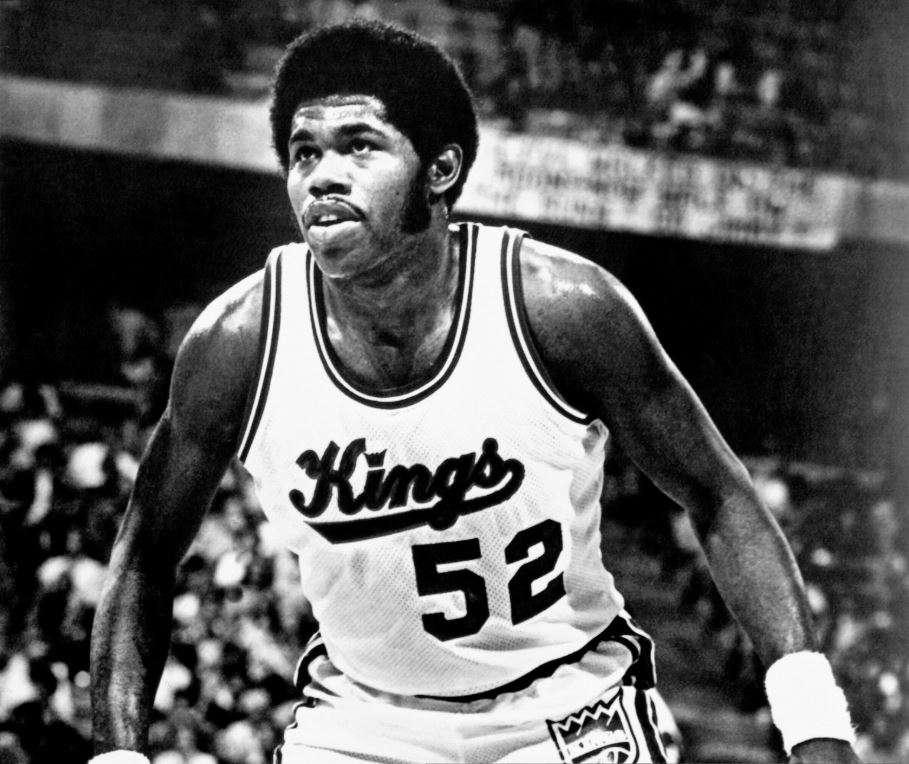

On a mediocre Kings team led by Tiny Archibald and Scott Wedman, both All Stars in 1975 76, Robinzine immediately found his place, splitting minutes at power forward with Larry McNeill. Bill was a wild dog on the court, standing out on the glass but also through constant fouling, and he quickly earned the label of an aggressive player, in a league that was far from gentle.

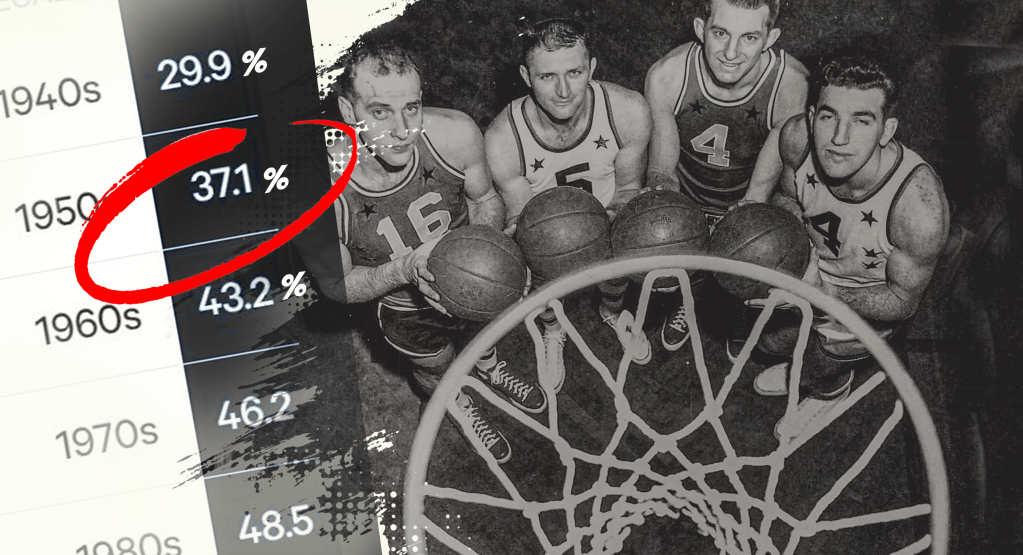

That year, he led the league in fouls per 100 possessions at close to 10, and rarely played more than 25 minutes for obvious reasons. A frustrating player, as he admitted himself, but one who made the most of his physique. A role player by nature.

Starting with his sophomore year, he earned a starting job on a Kings team that was improving, with the arrivals of Brian Taylor and Ron Boone, as the team moved toward a near .500 record. The next three seasons followed the same pattern, highlighted by two playoff appearances, both first round exits.

Whether under Phil Johnson, Larry Staverman, or Cotton Fitzsimmons, the Kings’ successive coaches in those years, Robinzine was a fixture in the paint, shining through his defense and his ability to steal possessions with offensive rebounds, despite being relatively small for the role at 201 cm. Even if he often had to be pulled because of fouls, he played 245 of the 246 games in his final three seasons in Kansas City.

Injury, trades, and decline

Late in the 1979 80 season, Robinzine hurt his leg while diving horizontally for an offensive rebound. He finished the year and even played in all three of Kansas City’s playoff games, but the injury proved more serious than expected. He was told that if he stayed, it would be as the backup to the promising Reggie King, drafted the year before.

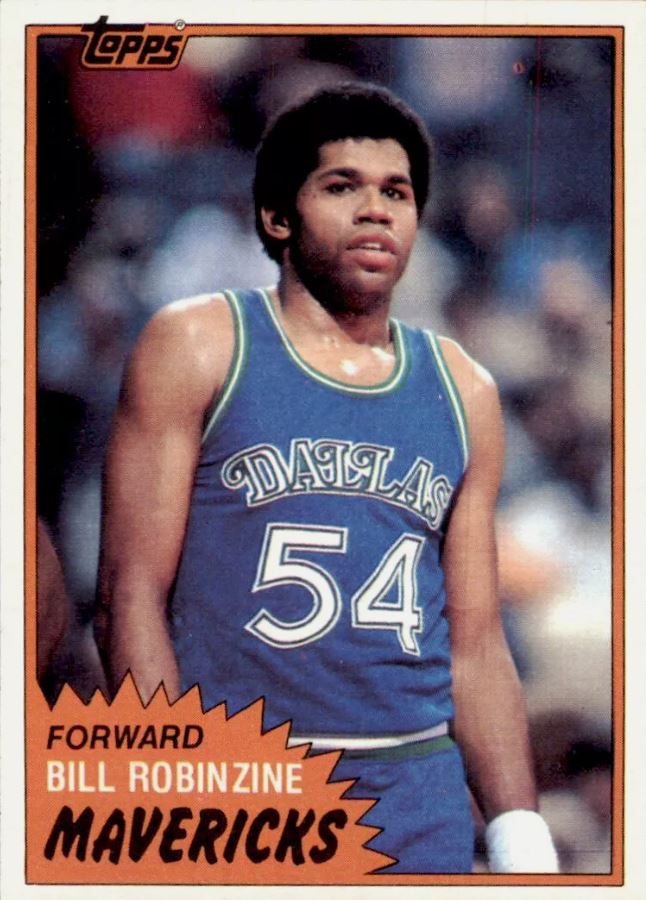

Before the 1980-81 season, he was traded to Cleveland, where he played only eight games before being sent a month later in a second deal, this time to Dallas, the league’s brand new franchise, coached by the eccentric Dick Motta. The team won only 15 games in its first year, but Bill played 70 of them, averaging 14 points and 7 rebounds, sharing his position with Tom LaGarde, who had come from Seattle. Even so, he was traded again the following summer, to Utah for Wayne Cooper.

In Utah, still limited by the leg injury, Robinzine became a rotation player, scraping together about ten minutes a night over 56 games in 1981 82. Frank Layden, the Jazz’s legendary head coach and president, did not renew his contract, and Bill hit free agency in the summer of 1982. He spent his summer training, but he told his agent and friend Robert Mann that he could not see himself having to prove himself again in a training camp, which was inevitable, since no NBA offer had come.

The anxiety of life after basketball, and suicide by carbon monoxide poisoning

On September 16, 1982, the Robinzine patriarch, Bill Sr., made the grim discovery. In a Kansas City garage, he found his son slumped behind the wheel of his Oldsmobile Toronado. The verdict was clear: suicide by carbon monoxide poisoning, a common method in the 1970s and 1980s.

For those around him, the shock was total. No warning signs had been detected before the tragedy. His closest friend in Kansas City, Tom Jones, said:

“He showed nothing. He wanted to appear strong. Bill, without basketball, could not continue to live the way he wanted. He was beginning to worry about not finding another team. What had started as a small part of his life had become enormous, and that’s when the financial problems appeared.“

Only his wife, Claudia, knew about her husband’s anxiety over a future that was still unclear. She was the one who called the police to report him missing when she came home and found an alarming note from him on the dining table. Two handwritten pages, showing a depressed state, but with no mention of suicide. Still close with Ray Meyer, his college coach, Bill showed no public sign of distress:

“He was all smiles. He never talked to us about his problems. But when I called his wife after his death, she told me he couldn’t come to terms with no longer being in the NBA.“

If Bill had financial difficulties, they were temporary and far from insurmountable, according to his lawyer and agent Robert Mann. Bill had a nice house in Kansas City worth $140,000, and an ongoing loan on a smaller house north of Dallas, bought at an inflated price and very clearly a real estate scam.

Even though the Mavericks’ front office had warned him the team was under construction and that no contracts were guaranteed, Bill fell into the trap of local investments set by unscrupulous real estate agents, seeing the dollars of new pro athletes in their city. But Mann insists no one was about to seize his mortgage. Bankruptcy was not on the horizon.

In 1981, his yearly salary was around $200,000. If his NBA future was uncertain, his resume, seven full seasons at close to 11 points and 6.5 rebounds a game, would have guaranteed him, even physically diminished, another professional team outside the NBA. Europe was watching his profile. In the summer of 1982, he was in contact with Italian clubs, which he turned down. He did not see himself leaving the country, especially since the offers were far below his previous NBA pay.

But the reality is that if NBA options still existed, they were for a much smaller role, and therefore a much smaller contract than before. Charles Grantham, vice president of the NBA Players Association at the time, said about the loss of one of his members:

“Most players think they can hang on a little longer. One more season. Convince another team. Then reality sets in.“

In the weeks after leaving the Jazz, Bill Robinzine did not consider quitting basketball despite the leg injury, to the frustration of his father, who saw the situation clearly. He preferred to steer the conversation toward music, or, on the edge of a smile, toward a plan to go into real estate.

Asked by a St Joseph Gazette reporter in 1979 what he imagined for life after basketball, Bill answered naively, “I hope I make enough money during my career that I will not have to do anything for the rest of my life.”

A prophecy that proved exact and cruel. When his death was announced, only the New York Times honored his memory with a detailed article published soon after, along with a strong piece in the Austin American-Statesman. Most of the quotes in today’s article come from those sources, as well as The Afro American on September 25, 1982, which ran a short item about his death.

Forgotten among the forgotten, Bill Robinzine could not endure the uncertainty of a career whose future was coming into view only in dotted lines. After seven very solid NBA seasons, he chose his exit through a fatal act, before he turned thirty.

Leave a comment